The Murder of Fr James Callaghan, 1921

The following is taken from a handwritten account of the events of 15th May 1921 witnessed by Mrs Kate Ms Sweeney, nee Kearney of Carraganaine, Macroom . The account is handwritten by Seosamh Ó Drisceoil, who was married to her niece Peig Kearney, also of Derrivane, Inchigeela. It is consistent with the account published in the Southern Star on Saturday 8 May 1976 shortly after her death, also written by Seosamh Ó Drisceoil. The Southern Star Account which provides some additional information is given below.

Cait Kearney Derrivane, Inchigeela in the Parish of Eve Laoghaire was house keeper for the Rev. James O’Callaghan R.I.P. for a period of 14 years. 4 years at Evelaoghaire Parise and being transferred to Ballingeary and to the Irish College took up residence at Mrs Lucey’s for a further 4 years and was then appointed curate at the North Cathedral in 1911. He continued his religious duties there until 1920 when he was transferred to the Clogheen Parish and the Good Shepard Convent. As that Parish was without a residence he was offered accommodation at Liam De Róiste’s of No 2 Upper Jane mount and resided there until his tragic death. R.I.P.

Between the night and morning of May 15th, 1921we were awakened at Liam De Róiste’s house with loud knocking, we got out of bed and his Reverence partly clad went to the window and opened it and spoke to the Tans, saying “ I am only a priest and a guest in this house” but then the crowd got angry and banged at the door, an then I put my head out the window and said “there is nobody here only 3 girls. You can’t expect us to open the door at this hour of the night”, and then again they said,” come down and open the door”. I returned from the window and came down the stairs and at that moment, he, the Tan, butted in the glass door and came in and up the stairs. I reached them and stood by the Priest. As the Tan came up the stairs he had a cap on his head and a scarf on his neck. I put up my hand to pull off the cap and scarf and was not able to do so. I said to them “This is Fr O’Callaghan, you won’t shoot him”. He drilled towards me and the Priest went backwards a few steps. The Tan followed him and pulled him to the bedroom door. I saw him prepare the revolver and I grasped it by the muzzle and as I did one shot rang out against the partition. He shook the revolver out of my grasp and pulled over the Priest and shot him through the spine and paralyzed him, he fell on the corridor, the Tan walked down the stairs and away.

The Priest was removed to the North Infirmary and died on Whit Sunday evening at 6 o’clock.

May 15th 1921. R.I.P.

Southern Star, Saturday 8 May 1976

Memories of 1921 recalled

Her many friends will mourn the passing away of that venerable old lady, Mrs Katie McSweeney, of Carriganine, Macroom, who was laid to rest in her native Inchigeela, on Sunday , April 11. Her death severs one of the last links with the murder by the Tans of Rev. James Callaghan, C.C. , Clogheen, Cork , on Whit Sunday, May 15, 1921.

As Katie Kearney she served Fr James Callaghan as housekeeper for fourteen years, from the time he was curate in the Úibh Laoghaire Parish in the first decade of the century, moving with him to the North Cathedral Parish in Cork in 1917 and from there to Clogheen Parish in 1920.

Since there was no accommodation for him in the new parish he was offered rooms in the house of Alderman Liam de Róiste in Upper Janemount. Alderman Liam de Róiste was a marked man, because of his involvement in the events of the day and was rarely at home.

In the early hours of Whit Sunday, May 15, 1921, a party of Tans surrounded the house. The partly clad priest opened his bedroom window and spoke to them. He informed them that he was a guest in the house and that Liam de Róiste was not at home. He told them that the only other occupants of the house were his housekeeper, Katie Kearney and two other girls. Miss Kearney then spoke to the Tans and begged them to leave the place but the leader of the party butted in the glass door with his rifle and rushed up the stairs. Miss Kearney grappled with him and in the ensuing melee a bullet was discharged grazing her hand. The priest retreated to his bedroom, followed by the Tan who shot him through the back several times. He fell to the floor paralyzed.

The Tan retreated, and the party moved off. Miss Kearney rushed out in her night attire to summon spiritual and temporal aid for the dying priest. He was removed to the North Infirmary Hospital where he died later that day.

That terrible ordeal left an indelible mark on the life of this refined lady. She often repeated the details of that tragic experience by her fireside at Carraganaine to interested listeners, as if she were reliving the episode.

After a long and faithful lif , she was called to join her beloved pastor at the age of 93. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a h-anam uasal.

The Educational Value of Games, a lecture given by Seosamh Ó Drisceoil N.T. in 1954

Nine years ago I took up my first teaching post in a medium sized city school in one of the poorer areas of Dublin. Like many schools in such places it was just a school, a place when children were doomed to spend ten to eleven years of their lives to acquire the minimum educational standard that would get them through life. It was a school without a tradition, if you could say that fully about a school, a school without colour or personality, in short a school without a soul. It was a school that never had its own football or hurling team, its own band or choir, its own dramatic or dancing class – it had none of those activities around which a school builds up a tradition that builds on and gives a certain personality to it, that builds on and gives a good and just pride in those who come in contact with it and makes it more than a drab uninteresting factory of education. The children, as a result, suffered from an inferiority complex that must have had a serious effect on their after lives.

When I introduced games in the place I never once thought they could have had such an effect, not alone on the school but on the neighbourhood. I must admit that my motive was a personal one – a devotion to the ideals of the G.A.A., and a desire to spread them in the City. Of course the Primary Schools League had long been in existence and was ready to help but I knew nothing about it. When I look back on the years and what a change has been wrought in the place I am convinced that it is difficult to overestimate the educational value of games.

Physical training is not formally taught in our school apart from the usual directions in correct walking, standing and sitting by the individual teacher in his own classes. In an official report of the Council of Education it is stated that the members are unanimous as to the necessity of physical training but could not agree on the amount, or method of instruction to be used. Games are, to the normal child, the best and most natural form of physical training. Not all children, however, can actively take part in games which aid physical growth. The child is a unit and the mental and physical should not be separated, the one ignored while the other is highly developed. Both parts are complementary and should be developed side by side, otherwise the child’s training will be off balance. Every education system should recognise the interdependence of body and mind. In every healthy, normal child there is an unconquerable desire for movement and games. Rather than supress or kill this desire we should follow the general principal followed in other aspects of education by cashing in on the desire of the child and using it to our own end. The transition from unlimited freedom of the home to the sedentary work of the school comes as a shock to the child. Organized games and systemized playing can ease this shock and remove much of the strain from the child’s life in school.

Games, if properly used cultivate a spirit of time and childhood sportsmanship. Success in this direction has little to do with direct teaching; it depends largely on the general tone and atmosphere of the school. The teacher’s own example is a most potent factor, and the more closely he is able to identify himself with the children’s playtime interests, the more influence he is likely to have.

We must take games seriously if we desire good results. What I mean here by seriously is that the instruction and guidance should be regular and well planned like that of other activities. Unless the teacher aims at developing in his pupils a satisfactory degree of skill and proficiency in the playing of games, the games themselves have little educational value whether for the purpose of immediate training or as a means of implanting a love of games for rational and healthy recreation in after life.

Games provide a necessary outlet for the natural impulse and the real but easy discipline associated with them is one of the best means of training the will in self-management. This influence on discipline will be noticed in the class room. But the other effect is of much greater importance because it is self-discipline when the child is most free and less removed from ordinary life than when he is in school, and it should help him considerably in later life. As well as self-control, self-respect, courage, devotion, good temper and a source of well-being, qualities that are desirable in the future citizen, are promoted when the body as well as the mind are rightly educated. Moreover, the necessity for combined effort and prompt co-operation on the part of the individuals who play games are of value in the community in promoting and fostering a healthy public spirit.

It is generally accepted today that the Greeks and Romans over emphasized the importance of games and physical instruction in their educational systems for in fact they based their systems on physical instruction. Yet who can doubt Plato’s philosophy when he says “the conduct of a man in his exercise, is a very important test of his character, and those who establish a system of education in music and gymnastics are not actuated by the purpose of applying the one to the improvement of the soul and the other to that of the body. They introduce both for the sake of the soul”. We see here how well the Greeks understood the educational value of games. We have all found as we move through life that one of our greatest needs is an inter-relation of the functions of the body and mind so that they may become harmonious. So great was the interest taken in this fundamental aspect of Greek education, that many of the great educationalists in the last century based their ‘new’ systems of education on the physical.

I made many blunders when I took on these games in our school because of my lack of a proper object in the work and because of my in-experience. I plunged the children into organised games of hurling and football with all their complications before the powers if co –ordination between brain and muscle were sufficiently developed and trained. That first effort resulted in failure as I had to plan my exercises and develop a well-planned system as I would in history or literature but of course less rigid.

I pointed out before that the school locality was one of the poorest in Dublin so the problem of providing proper equipment especially for hurling gave rise to a serious task. By various means I collected a good sum of money and gave out sticks, knicks, socks etc to the boys. I soon learned that most boys had little respect for the things which they got easily and not alone did they abuse the goods but soon they refused to pay their own bus fares or make any sacrifice whatsoever. Even some of them demanded money or other rewards before they would play. Things got so bad that I had to suspend games for a whole year and work out some other system of helping them in their financial difficulty. The obvious one was to subsidise the cost of the articles, always insisting that the child paid his share and made a sacrifice to get the article. I found that this system has worked well ever since.

Then we had the problem of defeat and victory and the training of a proper attitude in each. Victory came our way too easily and rather quickly. We had not earned it and so the result was an over dose of self-confidence and pride. It is very hard to guard against the depression that follows defeat in the over confidence in victory in the early stages. This only comes to a child with years of experience when he sees himself fit in as a very ordinary boy in life round about him.

I have noticed vary often that the headstrong child in the class room finds school life dull and uninteresting. He loses a certain amount of self-respect unless he is taken very carefully. But it is not unusual for these children to be particularly good at games and thereby winning the respect of the other boys. I have found this to have a very moderating effect on the tone of the class.

Games then should find a place in every school, habituating the child to self-control and self-reliance, obedience and co-operation and an easy friendly disposition as well as aiding physical growth. Opportunity for such training must be given by the school, for it must be remembered that all children, even those being brought up under healthy conditions with opportunities for play and bodily exercise, spend the best hours of the day at work in school – hours when light and sun are strongest and when their potential energy is at its greatest. Circumstances in the home, especially in the cities and large towns diminish their chances of making their bodies strong and healthy and the school must therefore afford them every opportunity it can for full development. This problem is one that must get full consideration in the planning and erecting of schools, especially in built up areas. Looking around at the amount that is being done under the direction of the Primary Schools League, one can only guess at what might be the result if proper facilities were available to all schools. In my school we have a hard surfaced yard 18ft by 60ft to accommodate three hundred children. This means that we are expected to travel three miles to Herbert Park where only limited facilities are available. No new school should be erected without a suitable playing space near at hand.

The question of indoor accommodation is also important as much of the finer training in ball control etc. could be carried out when outdoor exercise is undesirable owing to inclement weather or bad ground conditions. Much preparatory work could be overcome in this way but it should not take from the outdoor training in hard cold weather which serves the very important point of building up the child’s resistance. Regular lessons in games are necessary if they are to be of the utmost benefit to the pupils. Indoor, as well as outdoor facilities would make this possible.

In conclusion I would like to draw attention to another if indirect educational value that could be derived from games and something that I am keenly interested in. In our schools we are faced with the almost impossible task of reviving the Irish Language or should I say of spreading it since it is very much a living tongue in parts of my country yet, buíochas le Dia. We have all found in our teaching experience that if you link the matter to be learned with some pleasurable activity the children assimilate the matter more quickly and much of the slavery of other methods is avoided. From my own experience in the area of Irish on the playing field I have found that many children have grown to like the language because they at first associate it with the game which they enjoy playing. As the child matures the real motives which should inspire him to carry on the study of his native language should be explained to him.

Let us foster a love of our native games in the young hearts of the future generations of Irishmen and take to ourselves one more the motto of the Fianna of old” Glainne in ár gcroidthe, neart ‘nar lámha agus beart de réir ár mbriathar”.

Dialann mo Mháthair My Mothers Diary

By Fachtna Ó Drisceoil born 1972 ( son of Seosamh and his wife Peigí who died in 2001)

The inscription in my mother’s writing on the inside cover of the diary reads: “Leabhar Shéamais Fhionnbarr, agus Bhríde agus Dhéagláin agus Cholmáin” - then there is an empty space followed by a question mark and then - “agus Fachtna.” Myself, the youngest of five. The empty space represents the brother or sister that could have been, but died in my mother’s womb. Strangely, she does not refer anywhere else in the diary to this loss. Yet that empty space between my nearest brother and myself seems more powerful than any written words.

My parents started keeping the diary in September 1960 after the birth of my eldest brother. “Rugadh Séamus Fionnbharr fé dheabhadh timpeall 9 iar nóin ar an gCéadaoin 21 Méan Fómhar 1960.” Many of the early entries are in my father’s scrawled penmanship but my mother’s more legible schoolteacher’s writing soon takes over. Both are in the beautiful old Gaelic script for the first few years. The diary is a battered A4 size hardback ledger, the pages yellowed and stained with age and use.

The proud parents record the daily progress of their first child: “An 9ú Feabhra 1961: Dúirt Séamus ga-ga. An 10ú Feabhra: Dúirt sé at at agus ba.” But of course like all new parents they had their difficulties: “An 16ú Feabhra 1961. É millte dár linn le iomarca notice. Lig Mamaí dó gol inniu agus stad sé. É go maith ina dhiaidh.”

Most of the entries are quite matter of fact descriptions of every little event in the new baby’s life. Now and again the young mother’s excitement and pride bursts through the mundane details. The first birthday is announced in large excuberent capital letters. “Lá breithe, bliain d’aois. Sceitimíní ar Mhamaí faoin lá. Í ag tnúth go mór leis.” The presents from neighbours and relations reflect an Ireland far-removed from the Celtic Tiger. “Punt ón Godmother, punt ó Mrs Rodgers, bróga is stocaí ó Nanny, brístí ó Mháire agus Jimmy.” The excitement intensifies when Séamus, with a great sense of timing that bodes well for later life, chooses the day of his birthday to stand for the first time on his own two feet. As the day draws to a close my mother reflects: “Bliain ó anois ag 9pm a rugadh é. A lán cártaí. Brón ar Mhamaí go bhfuil an lá thart.”

Very little in the later years of the diary matches the excitement of that first year or two. When my sister Bríd is born her entry into the world is simply recorded: “5 Meán Fómhair. Glaoch ag Mom go Holles Street. Bríd Carmel ar an saol ar 2.30pm Dé Céadaoin.” My brothers Déaglán and Colmán follow in 1965 and 67.

The most animated entry in these years, concerns the 50th anniversay of the 1916 rising. How our country has changed, and changed utterly since those more innocent days, when even a Fine Gael household like ours could embrace this event with enthusiasm. “Sprid iontach ag borradh le mí anuas. Séamus ag cur aithne ar na Signatories tré pictiúrí agus nuachtáin. P.H. Pearse ar aithne aige. Tomás Ó Cleirigh, Seán Mac Diarmada &rl. É lán de chaint i dtaobh saighdiurí na hÉireann. Brat na hÉireann aige. É ag canadh Wrap the Green Flag round me.” My father put aside four 1916 commemorative coins in order to present them to his children on their wedding days. He didn’t keep one for me as my parents had neither conceived me, nor conceived of me at that time. I was not born until the feast of the epiphany 1972. My mother simply states: “Rugadh Fachtna. Buíochas le Dia.” Whether that was gratitude or simply relief I’m not sure. My sister Bríd, the only girl in the family cried at the arrival of yet another boy. She wasn’t the last woman I was to reduce to tears.

My mother was not as diligent in keeping the diary up to date in later years and the entries are more infrequent. In September 2000 she was diagnosed with stomach cancer: “13 Deireadh Fomhair 2000: Cuireadh mé faoi scian. Ní raibh sé sásúil. Secondaries sa bhealach.”

“Tús na Samhna. Chemo go ceann 6 mhí. Mé ag déanamh go maith as.”

She died in Harolds Cross Hospice on the last day of April 2001. The last entry in the diary on the 23rd of December 2000 concerns the death of her brother Dan and the mid-winter journey to his funeral in West Cork: “Cuireadh é in Inse Geimhleach. Bhí an tír faoi shneachta, sioc agus leac-oighear…”

After that the remaining pages of the diary are blank. Once more the empty space says more than words can. Some absences will always remain unfilled.

My quest for stardom. By Fachtna Ó Drisceoil ( youngest son of Seosamh born 1972 )

John Simpson, Kate Adie, Charlie Bird… and now me. I had landed a job as a reporter with the fledgling Teilifís na Gaeilge, and I was going to be famous. I remember asking my new boss for advice on how to cope with the public attention. He nodded gravely behind his designer sunglasses and told me that I would have to watch my behaviour in public from now on. Whether he was humouring me or really believed that his protegés would become household names, I’m not quite sure. Ach ní mar a shíltear a bítear. Apart from Connemara and Irish language gatherings, I travelled all over the West of Ireland in my role as roving reporter in perfect anonymity. No autograph hunters, no requests to pose for photographs, no star-struck cailíní deasa.

As that first winter on the road set in, the glamour was well and truly banished from the job. Ár dtuairisceoir Fachtna Ó Drisceoil, spent shivering hours on end standing in bogs and on mountainsides, innapropriately and insufficiently attired in suit and tie. On one particulatary bitter winter’s day - bhí sé ina ghála agus ag stealladh báistí - I was sent out to a remote Connemara outpost to do a report on the topic of fish farming. When the time came to do my piece to camera cois farraige agus i lár na doinnine, I decided not to remove the protection of my green tweed cap. Back at base a few of my colleagues commented favourably on my slightly quirky appearance for a news reporter. The boss took a different view. “Ní theastaíonn uaim an caipín a sin a fheicáil riamh arís,” a dúirt sé. The tweed cap was banned from T na G. This was the final indignity. I was mad as hell, and I wasn’t taking it anymore.

Far from dissapearing from the nation’s TV screens, I resolved that my caipín bréidín would appear in almost all my newsreports, as a kind of Hitchcockian visual signature. My fellow reporters and cameramen became part of the conspiracy. If you looked hard enough, you would see the cap behind me on a wall, hanging from a tree, or maybe just poking out of my coat pocket. It became a regular competition in the newsroom to see who could spot the caipín. Gradually we became bolder. As I did a piece to camera in front of a schoolyard of playing children, one of them bizarrely enough, was wearing a green tweed cap. On another occasion I was talking to camera in front of a group of anti-mobile phone mast protesters. The cameraman persuaded one of those walking up and down behind me to don the green cap. Our most daring episode involved an actual interviewee wearing my cap.

Eventually at the Christmas party, as I sat at a table with the boss, a drunken colleague revealed my secret. It would have come out sooner or later anyway, and the Christmas party was probably the best time for it to happen, what with peace and goodwill to all mankind and all of that. The boss took it in good humour, but the era of the green cap on T na G had come to an end.

I took to the roads of the West again. Béal an Átha, Dúlainn, An Caiseal, Baile Átha an RÍ, Cora Droma Rúisc. I reportered from all these places and more, without so much as a ripple of recognition from the local populace for the TV star in their midst. And then one day, in late August, I was sent to Castlebar to do a report on the build up to the All-Ireland football final, which featured Mayo that year. The place was gone mad with houses, cars, shopfonts and even faces painted red and green. And on that day for the first time I saw strangers pointing at me on the street and heard them saying “Look, there’s yer man in the cap from T na G.” Like Johnny Logan who was said to be big in Turkey, I was big… in Castlebar.

Fachtna

Cape Clear Adventure 1993 by Fachtna Ó Drisceoil

I tread water silently in the starlit waters of the natural Harbour. Suddenly the rusty roar of a much abused car engine shatters the silence, as it accelerates up the steep road towards the centre of the island. The sound recedes and serenity is restored once more. I am alone, floating in the midnight waters of Cape Clear’s South Harbour. The year is 1993 and for the third summer I am the warden of Cuas an Uisce, the small campsite located on the shore of the scenically stunning Cuan Theas. The campsite is comprised of several levels, each lower than the one before it, as you move down towards the water. The final and lowest level is out of sight of all the others, and you can clamber down further still onto the rocks at the waters edge. It is here that I remove my clothing and tread carefully into the cool waters for my nocturnal swims. The electrifying rush of water on naked flesh, the hauntingly beautiful atmosphere of the silent bay, draw me back night after night.

Years before, my childhood instructor despaired of ever teaching me to swim properly. While the children all around me in the pool grew more confident as they dived into the deep end, I never managed more a few strokes at a time before having to support myself on my feet. By my teenage years I had accepted that I was never going to learn to swim properly. And then, as a university student, I got the job of campsite warden on Oiléan Chléire or Cape Clear off the coast of West Cork, where I met a beautiful young trainee teacher working as a cinnire in the island’s Coláiste Samhraidh. Among her many talents she was a trained lifeguard who thought it a great shame that I was unable to fully appreciate the island’s bathing spots. With great persistance and skill, she helped me to overcome whatever mental block had stopped me in childhood from learning to swim, and in no time at all I was happily treading water and doing the breaststroke out of my own depth. The fact that I was strongly attracted to my instructor made spending time with her on the beach no great hardship at all, and we went on to have a summer romance which I still remember with fondness.

On another summer visit to Cape Clear, after my time as campsite warden, I realized to my dismay that I had forgetton to bring my swimming togs. It was a beautiful sunny day and I was not going to forgo the pleasure of my favourite swimming spot, so I slipped into the waters at Cuas an Uisce in my underpants. As I swam out into the South Harbour I noticed a floating buoy some distance out and decided in my mind to make it my destination. When I reached the buoy I still felt quite energetic and noticed another buoy further out, so I decided to make for it. Upon reaching the second buoy I realized I was now halfway out into the harbour, and sure, twas just as easy to swim on to the other side, as it was to return the way I had come. And so on I went, continuing what for me was a swim of epic proportions, a feat I had never achieved before. As I pulled myself out of the water on the far side of the harbour, I felt a tremendous sense of well being and achievment… until the reality of my situation set in. I was now far too exhausted to swim safely back across the harbour, and the only way to get to my clothes was a fifteen minute walk along a stony public road in my bare feet and wearing only my y-fronts. There was no other option but to brazen it out. With a fixed smile on my face and what I hoped was an air of insouciance, I greeted the startled walkers and drivers I encountered on my painful and painfully embarrasing trek around the harbour.

The spectacle passes and I remember once more my naked nighttime swims in the South Harbour. Even imagining myself there now helps to bring a sense of calm and contentment. As I look up at the stars above me I am very aware that I am alone in a small bay, on the south side of an island, off the south west coast of another island, on the edge of a continent, on a small planet floating on a starlit sea. Ahhh…. Now where did I leave my clothes?

Paddy O Driscoll (1920-2001) and the DDay Landings , For want of a nail

For the want of a nail, the battle was lost, according to the famous poem.

But when our Uncle Paddy O’Driscoll, was the metaphorical nail, there was no such mishap, and one of the greatest battles in modern times came to be won!.

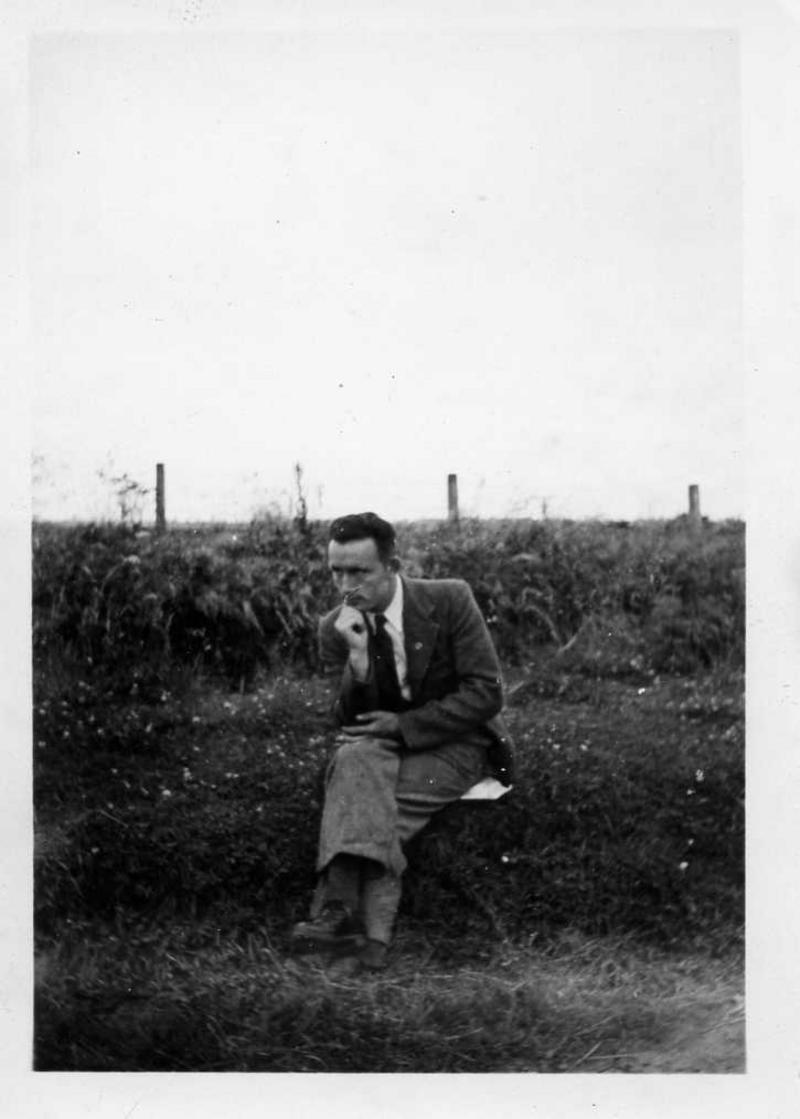

This is a photo of my Paddy, of Dunbeacon, Durrus, Co Cork taken in 1948. Paddy worked his entire life in the Post Office and during WW11 was a telegraph operator in the GPO. This was a strategic wartime communications role and he was subject to the Official Secrets Act.

Early in the War, an invasion hoax had been  perpetuated causing the mobilisation of the Irish Army. Paddy was, for a while, wrongly suspected and was suspended before being completely exonerated.

perpetuated causing the mobilisation of the Irish Army. Paddy was, for a while, wrongly suspected and was suspended before being completely exonerated.

One of his tasks was to collate the reports from the various Irish weather stations, to transcribe these into Morse code and to forward them by telegraph to the UK. His office also contained a phone which was almost never used.

One day, shortly after forwarding the forecast as usual the phone rang and Paddy found himself talking to a person with a “clipped upper class English accent” who did not identify himself.

The caller asked Paddy to confirm who he was and that he had sent the recent forecast. He was then asked him to recheck all his information carefully and to resend the forecast.

Given his earlier experience, Paddy did so with great trepidation, thinking perhaps that he had made some terrible mistake. He found that the reports had been correctly transcribed and resent the same forecast again.

Little did he know as he cycled home that evening that it was the eve of the D. Day Normandy Landings, already delayed due to bad weather and that their success were in large part attributed to the element of surprise caused by the better weather forecasts of the Allies. Ireland’s part in providing that vital information was not acknowledged until very recently and Paddy only revealed his part to me late in life.

And so, I think it is fair to say to our Uncle Paddy, a lowly Post Office clerk was a small but nevertheless vital cog in the greatest seaborne invasion in history.

Paddy O’Driscoll, 1920-2001, RIP.